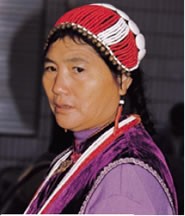

Anong in Myanmar (Burma)

Photo Source:

Copyrighted © 2026

Asia Harvest-Operation Myanmar All rights reserved. Used with permission |

Send Joshua Project a map of this people group.

|

| People Name: | Anong |

| Country: | Myanmar (Burma) |

| 10/40 Window: | Yes |

| Population: | 11,000 |

| World Population: | 19,100 |

| Primary Language: | Anong |

| Primary Religion: | Ethnic Religions |

| Christian Adherents: | 40.00 % |

| Evangelicals: | 4.00 % |

| Scripture: | Complete Bible |

| Ministry Resources: | No |

| Jesus Film: | No |

| Audio Recordings: | Yes |

| People Cluster: | Tibeto-Burman, other |

| Affinity Bloc: | Tibetan-Himalayan Peoples |

| Progress Level: |

|

Identity

The Anong have been recognized as a distinct tribe in Myanmar for almost a century, with the 1931 census returning 107 "Nung" people. Identifying them is complicated by the fact that they overlap with the related Rawang tribe in the same part of the country. Some scholars say the Anong are one of five main Rawang clans. The Anong also share many cultural similarities to the large and well-known Lisu tribe.

Location: With a population of 11,000 people in Myanmar, the Anong tribe dwells in the northernmost part of the country, throughout the three districts of Putao, Myitkyina, and Tanai in Kachin State. Majestic snowcapped mountains create a barrier between the Anong area and the Chinese provinces of Yunnan and Tibet to the north. Most Anong people live in China, where they are officially known as the Nu nationality. They boasted a population of over 36,000 people according to the 2020 Chinese census.

Language: Although the Anong in China and Myanmar speak different dialects, people in each country report no difficulty communicating with each other. In China, linguists have labeled the Anong language “moribund” (at the point of death), with only about 50 elderly people out of a population of 36,000 still able to speak it. The language is also fading into obscurity in Myanmar, with approximately 400 people still able to speak it. Most tribe members seem unconcerned about losing their language and are speaking Lisu or Rawang instead.

History

Before their conversion to Christianity, the Lisu often bullied the Anong in China's Salween Valley. The Lisu would frequently place a corpse on Anong land and claim the Anong had committed murder. “The demand for compensation, called oupuguya, was imposed. This tyrannous annual exaction would be paid continuously for several generations. Each Anong village usually would have to pay six to eight such iniquitous taxes each year.”

Customs

A National Geographic researcher visited the Anong people in 1926 and noted that the men were highly skilled hunters and adept at using crossbows: “Every little boy carries his bow and arrow and every living creature, from the smallest bird to the bear or traveler, serves as a target. Their arrows are very strong, and the points are poisoned with the root of aconite.” The Anong traditionally made all their clothing from hemp, but today “almost all women adorn themselves with strings of coral, agate, shells, glass beads, and silver coins on their heads and chests.… In some areas, women adorn themselves in a unique way by winding a type of local vine around their heads, waists, and ankles.”

Religion

For many years the Anong on both sides of the border practiced a primitive form of Animism, while some families living near Tibetans were influenced by Buddhism. Each village and clan had its own shaman, who acted as a mediator between the community and the spirit world. The tribe experienced an upheaval in the first half of the 20th century when it was impacted by the arrival of Catholic and then Evangelical Christianity. Today, the majority of Anong people in Myanmar still cling to the animistic rituals of their forefathers, although professing Christians number approximately 40 percent of the population.

Christianity

A French Catholic priest named André escaped the 1905 massacre of Catholics at Deqen in China that was ordered by the Dalai Lama. He made his way to the Anong area in China and worked single-handedly among them for many years. Evangelical Christianity first reached the Anong on the Chinese side of the border when J. Russell Morse and his family worked in the Upper Salween area for 25 years prior to the expulsion of missionaries in 1949. Their mission base, described as “one of the most isolated stations in the world,” converted 6,900 Lisu and Nu people and established 74 churches. The Anong New Testament was first published in 1981, but the believers had to wait another 34 years before the full Bible was available in 2015.